basilh@virginia.edu

@basilhalperin

Until very recently – see last month's WSJ survey of economists – the FOMC was widely expected to raise the target federal funds rate this week at their September meeting. Whether or not the Fed should be raising rates is a question that has received much attention from a variety of angles. What I want to do in this post is answer that question from a very specific angle: the perspective of a New Keynesian economist.

Why the New Keynesian perspective? There is certainly a lot to fault in the New Keynesian model (see e.g. Josh Hendrickson). However, the New Keynesian framework dominates the Fed and other central banks across the world. If we take the New Keynesian approach seriously, we can see what policymakers should be doing according to their own preferred framework.

The punch line is that the Fed raising rates now is the exact opposite of what the New Keynesian model of a liquidity trap recommends.

If you're a New Keynesian, this is the critical moment in monetary policy. For New Keynesians, the zero lower bound can cause a recession, but need not result in a deep depression, as long as the central bank credibly promises to create an economic boom after the zero lower bound (ZLB) ceases to be binding.

That promise of future growth is sufficient to prevent a depression. If the central bank instead promises to return to business as normal as soon as the ZLB stops binding, the result is a deep depression while the economy is trapped at the ZLB, like we saw in 2008 and continue to see in Europe today. The Fed appears poised to validate earlier expectations that it would indeed return to business as normal.

If the New Keynesian model is accurate, this is extremely important. By not creating a boom today, the Fed is destroying any credibility it has for the next time we hit the ZLB (which will almost certainly occur during the next recession). It won't credibly be able to promise to create a boom after the recession ends, since everyone will remember that it did not do so after the 2008 recession.

The result, according to New Keynesian theory, will be another depression.

I. The theory: an overview of the New Keynesian liquidity trap

I have attached at the bottom of this post a reference sheet going into more detail on Eggertsson and Woodford (2003), the definitive paper on the New Keynesian liquidity trap. Here, I summarize at a high level –skip to section II if you are familiar with the model.

A. The NK model without a ZLB

Let's start by sketching the standard NK model without a zero lower bound, and then see how including the ZLB changes optimal monetary policy.

The basic canonical New Keynesian model of the economy has no zero lower bound on interest rates and thus no liquidity traps (in the NK context, a liquidity trap is defined as a period when the nominal interest rate is constrained at zero). Households earn income through labor and use that income to buy a variety of consumption goods and consume them to receive utility. Firms, which have some monopoly power, hire labor and sell goods to maximize their profits. Each period, a random selection of firms are not allowed to change their prices (Calvo price stickiness).

With this setup, the optimal monetary policy is to have the central bank manipulate the nominal interest rate such that the real interest rate matches the "natural interest rate," which is the interest rate which would prevail in the absence of economic frictions. The intuition is that by matching the actual interest rate to the "natural" one, the central bank causes the economy to behave as if there are no frictions, which is desirable.

In our basic environment without a ZLB, a policy of targeting zero percent inflation via a Taylor rule for the interest rate exactly achieves the goal of matching the real rate to the natural rate. Thus optimal monetary policy results in no inflation, no recessions, and everyone's the happiest that they could possibly be.

B. The NK liquidity trap

The New Keynesian model of a liquidity trap is exactly the same as the model described above, with one single additional equation: the nominal interest rate must always be greater than or equal to zero.

This small change has significant consequences. Whereas before zero inflation targeting made everyone happy, now such a policy can cause a severe depression.

The problem is that sometimes the interest rate should be less than zero, and the ZLB can prevent it from getting there. As in the canonical model without a ZLB, optimal monetary policy would still have the central bank match the real interest rate to the natural interest rate.

Now that we have a zero lower bound, however, if the central bank targets zero inflation, then the real interest rate won't be able to match the natural interest rate if the natural interest rate ever falls below zero!

And that, in one run-on sentence, is the New Keynesian liquidity trap.

Optimal policy is no longer zero inflation. The new optimal policy rule is considerably more complex and I refer you to the attached reference sheet for full details. But the essence of the idea is quite intuitive:

If the economy ever gets stuck at the ZLB, the central bank must promise that as soon as the ZLB is no longer binding it will create inflation and an economic boom.

The intuition behind this idea is that the promise of a future boom increases the inflation expectations of forward-looking households and firms. These increased inflation expectations reduce the real interest rate today. This in turn encourages consumption today, diminishing the depth of the recession today.

All this effect today despite the fact that the boom won't occur until perhaps far into the future! Expectations are important, indeed they are the essence of monetary policy.

C. An illustration of optimal policy

Eggertsson (2008) illustrates this principle nicely in the following simulation. Suppose the natural rate is below the ZLB for 15 quarters. The dashed line shows the response of the economy to a zero-inflation target, and the solid line the response to the optimal policy described above.

Under optimal policy (solid line), we see in the first panel that the interest rate is kept at zero even after period 15 when the ZLB ceases to bind. As a result, we see in panels two and three that the depth of the recession is reduced to almost zero under policy; there is no massive deflation; and there's a nice juicy boom after the liquidity trap ends.

In contrast, under the dashed line – which you can sort of think of as closer to the Fed's current history independent policy – there is deflation and economic disaster.

II. We're leaving the liquidity trap; where's our boom?

To be completely fair, we cannot yet say that the Fed has failed to follow its own model. We first must show that the ZLB only recently has ceased or will cease to be binding. Otherwise, a defender of the Fed could argue that the lower bound could have ceased to bind years ago, and the Fed has already held rates low for an extended period.

The problem for showing this is that estimating the natural interest rate is extremely challenging, as famously argued by Milton Friedman (1968). That said, several different models using varied estimation methodologies all point to the economy still being on the cusp of the ZLB, and thus the thesis of this post: the Fed is acting in serious error.

Consider, most tellingly, the New York Fed's own model! The NY Fed's medium-scale DSGE model is at its core the exact same as the basic canonical NK model described above, with a lot of bells and whistles grafted on. The calibrated model takes in a whole jumble of data – real GDP, financial market prices, consumption, the kitchen sink, forecast inflation, etc. – and spits outs economic forecasts.

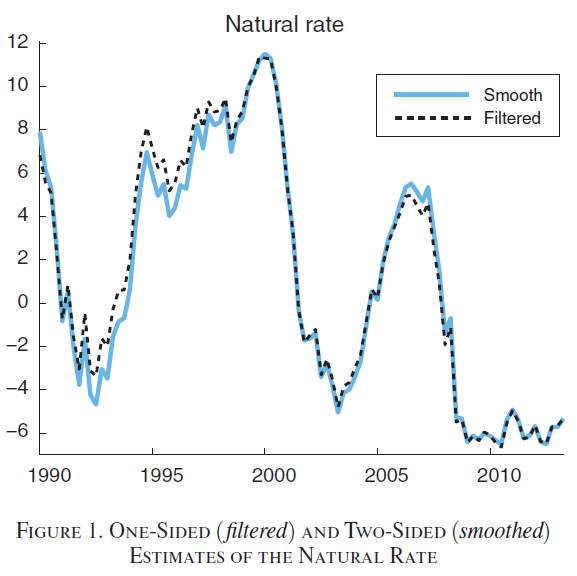

It can also tell us what it thinks the natural interest rate is. From the perspective of the New York Fed DSGE team, the economy is only just exiting the ZLB:

Barsky et al (2014) of the Chicago Fed perform a similar exercise with their own DSGE model and come to the same conclusion:

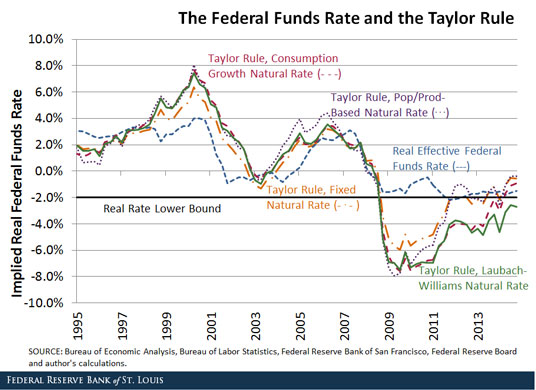

Instead of using a microfounded DSGE model, John Williams and Thomas Laubach, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco and director of monetary affairs of the Board of Governors respectively, use a reduced form model estimated using a Kalman filter. Their model has that the natural rate in fact still below its lower bound (in green):

David Beckworth has a cruder but more transparent regression model here and also finds that the economy remains on the cusp of the ZLB (in blue):

If anyone knows of any alternative estimates, I'd love to hear in the comments.

With this fact established, we have worked through the entire argument. To summarize:

III. What's the strongest possible counterargument?

I intend to conclude all future essays by considering the strongest possible counterarguments to my own. In this case, I see only two interesting critiques:

A. The NK model is junk

This argument is something I have a lot of sympathy for. Nonetheless, it is not a very useful point, for two reasons.

First, the NK model is the preferred model of Fed economists. As mentioned in the introduction, this is a useful exercise as the Fed's actions should be consistent with its method of thought. Or, its method of thought must change.

Second, other models give fairly similar results. Consider the more monetarist model of Auerbach and Obstfeld (2005) where the central bank's instrument is the money supply instead of the interest rate (I again attach my notes on the paper below).

Instead of prescribing that the Fed hold interest rates lower for longer as in Eggertsson and Woodford, Auerbach and Obstfeld's cash-in-advance model shows that to defeat a liquidity trap the Fed should promise a one-time permanent level expansion of the money supply. That is, the expansion must not be temporary: the Fed must continue to be "expansionary" even after the ZLB has ceased to be binding by keeping the money supply expanded.

This is not dissimilar in spirit to Eggertsson and Woodford's recommendation that the Fed continue to be "expansionary" even after the ZLB ceases to bind by keeping the nominal rate at zero.

B. The ZLB ceased to bind a long time ago

The second possible argument against my above indictment of the Fed is the argument that the natural rate has long since crossed the ZLB threshold and therefore the FOMC has targeted a zero interest rate for a sufficiently long time.

This is no doubt the strongest argument a New Keynesian Fed economist could make for raising rates now. That said, I am not convinced, partly because of the model estimations shown above. More convincing to me is the fact that we have not seen the boom that would accompany interest rates being below their natural rate. Inflation has been quite low and growth has certainly not boomed.

Ideally we'd have some sort of market measure of the natural rate (e.g. a prediction market). As a bit of an aside, as David Beckworth forcefully argues, it's a scandal that the Fed Board does not publish its own estimates of the natural rate. Such data would help settle this point.

I'll end things there. The New Keynesian model currently dominates macroeconomics, and its implications for whether or not the Fed should be raising rates in September are a resounding no. If you're an economist who finds value in the New Keynesian perspective, I'd be extremely curious to hear why you support raising rates in September if you do – or, if not, why you're not speaking up more loudly.