basilh@virginia.edu

@basilhalperin

TLDR:

---

When most people worry about recessions, they’re worried about involuntary unemployment. If we want to think about the role of monetary policy in recessions, then, it feels natural to worry about sticky wages.

In their heart of hearts, I think a lot of macroeconomists – and casual observers of macro – think sticky wages are in fact the most important reason for thinking about the role of monetary policy in recessions.

But in our baseline New Keynesian macroeconomic models, we think about price stickiness and not wage stickiness. In the baseline textbook monetary model, as in e.g. Gali/Woodford/Walsh, we work with a model of sticky prices as our base case; and only teach sticky wages as supplementary material.

Why?

Tracing the history of thought on this, going back to the advent of “new Keynesianism” in the 1980s, my takeaway is that:

The preference for sticky price models over sticky wage models is somewhat of a historical accident; in that the original critiques of sticky wage models are now broadly accepted to be incorrect.

One of the first papers to use the term “new Keynesian” (with a lowercase ‘n’, rather than the uppercase that is now used) was the Rotemberg (1987) Macro Annual paper on “The New Keynesian Microfoundations”. Here’s how he described what made this “new”:

“One might ask in all seriousness what is new about the current generation of Keynesian models. The major difference between the current and previous generations (Fischer 1977, Taylor 1980) is an emphasis on the behavior of product markets.”

As highlighted here by Rotemberg, in the mid-1980s there was a switch from the Fischer and Taylor sticky wage models (focusing on the labor market) to sticky price models (focusing on the product market).

If you think of high involuntary unemployment as being the defining feature of recessions, how do such sticky price models explain unemployment? As Mankiw explains in a comment on Rotemberg’s paper,

“Firms lay off workers in recessions not because labor costs are too high [due to nominal wage stickiness], but because sales are too low [due to goods price stickiness].”

That is: you weren’t fired from your job because you were “too stupid and too stubborn” to lower your wage demand. You were fired because your firm’s sales fell, and so they no longer needed to produce as much, and so didn’t need you. (See also: Barro and Grossman 1971 or the first half of Michaillat and Saez 2015.)

Unemployment, here, is the same phenomenon as a classical model: you chose to be unemployed because you preferred the leisure of Netflix compared to working for a lower real wage. More complicated models can and do add frictions that change this story – labor search frictions; sticky wages on top of sticky prices – but as a baseline, this is the logic and mechanism of these models.

Why was this switch to sticky price models made? With sticky wage models, by contrast, people are genuinely involuntarily unemployed – which again is plausibly the defining characteristic of recessions. Why switch away towards this muddier logic of sticky prices?

Two critiques of sticky wage models led to the adoption of sticky price models:

As we’ll get to in a bit, today no one (?) agrees with the empirical critique, and the theoretical critique both does not have real bite and is anyway typically ignored. First, a summary of each critique:

1. Arguably the strongest critique against sticky wage models at the time was the evidence that real wages don’t go up during recessions. After all, if unemployment is caused by real wages being too high – the price level has fallen but nominal wages cannot – then we should see real wages going up during recessions.

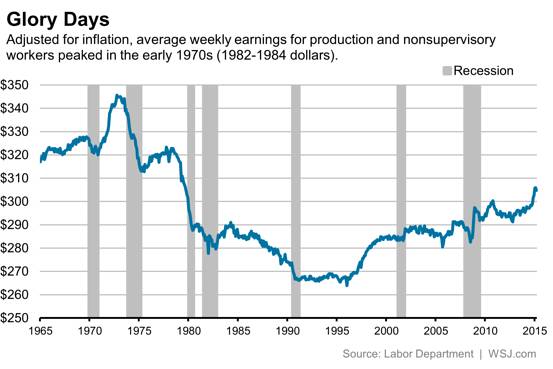

In the aggregate US data, this simply did not hold: depending on the time period and the deflator used, real wages could appear countercyclical as predicted, basically acyclical, or even procyclical. To get the general idea (we’ll quibble over measurement later) here’s a graph of a measure of real average hourly earnings I grabbed from the WSJ:

Average real wages are not strikingly obviously “too high” during recessions here – earnings don’t spike upward in the shaded areas – particularly when you look at the 1970s and 1980s.

2. The second, theoretical critique was advanced by Barro (1977) and described by Hall (1980). This argument is usually summarized as: employer-employee relationships could be implicitly long-term contracts, and so observed nominal wage stickiness in the short run need not imply allocative inefficiency.

For example, if I expect to produce $3 of (marginal) value this year and $1 next year, I don’t really care if my boss promises to pay me $2 in each year – even though this year I’m being paid less than my value.

Similarly, even if my nominal wages don’t fall during a recession, perhaps over my entire lifetime my total compensation falls appropriately; or, other margins adjust.

---

Arguably, price stickiness is not vulnerable to either of the above critiques of wage stickiness, and hence the appeal over wage stickiness:

Hence, the transition from sticky wage models to the dominance of sticky price models starting in the 1980s. Yun (1996) builds the full dynamic model with Calvo sticky pricing at the heart of the New Keynesian framework; Woodford, Gali, and Walsh organize NK thought into textbook format.

But – these critiques are at best incomplete and at worst conceptually incorrect. Here’s why:

“Observed real wages are not constant over the cycle, but neither do they exhibit consistent pro- or countercyclical tendencies. This suggests that any attempt to assign systematic real wage movements a central role in an explanation of business cycles is doomed to failure.”

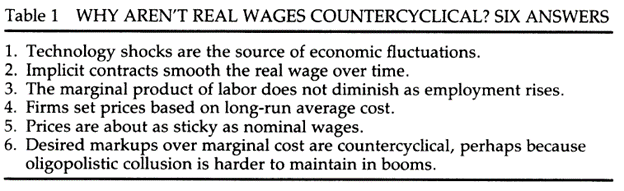

– Lucas (1977)Mankiw (1991) – another comment on a later Rotemberg Macro Annual paper coauthored with Woodford – writes: “As far as I know, there are six ways to explain the failure of real wages to move countercyclically over the business cycle... None of these explanations commands a consensus among macroeconomists, and none leaves me completely satisfied.” He offered this list of possible explanations:

I don’t want to go through each of these in detail – see Mankiw’s comment; and note some of these suggestions are pretty esoteric. Most of these are immediately unsatisfactory; on #2, implicit contracts, we’ll come back to.

The problem I want to highlight is that: the late-80s/early-90s understanding summarized in this table leaves out the three most compelling – and now widely-recognized – reasons that the cyclicality of the aggregate real wage is not diagnostic of the sticky wage model.

1. Identification: the source of the shock matters!

Recessions caused by tight monetary policy should cause real wages to increase and be too high, leading to involuntary unemployment. Recessions caused by real supply-side shocks should cause real wages to fall and nonemployment to rise.

If the economy experiences a mix of both, then on average the correlation of real wages and recessions could be anything.

Maybe in 1973 there’s an oil shock, which is a real supply-side shock: real wages fall and nonemployment rises (as in the data). Maybe in 2008 monetary policy is too tight: real wages spike and unemployment rises (as in the data). Averaging over the two, the relationship between real wages and unemployment is maybe approximately zero.

This view was around as early as Sumner and Silver (1989) JPE, where they take a proto-“sign restrictions” approach with US data and find procyclical real wages during the real shocks of the 1970s and countercyclical real wages during other recessions.

But: while Sumner-Silver was published in the JPE and racked up some citations, it seems clear that, for too long a time, this view did not penetrate enough skulls. Macroeconomists, I think it’s fair to say, were too careless for too long regarding the challenge of identification.

My sense is that this view is taken seriously now: e.g. in my second-year grad macro course, this was one of the main explanations given. At the risk of overclaiming, I would say that for anyone who has been trained post-credibility revolution, this view is simply obviously correct.

2. Composition bias: the measured real wage can be deceptive

Solon, Barsky, and Parker (1994) QJE make another vitally important point.

The combination of (1) and (2) implies that a measurement of aggregate real wages of employed workers will be biased upwards during recessions. (This happened in 2020, too; source)

Thus adjusting for this composition bias – as long as (2) continues to hold – causes you to realize that the more conceptually correct “shadow aggregate average real wage” is even lower, not higher, during recessions. It does point out, however, that the measured aggregate real wage is simply not the right object to look at!

(For the most comprehensive analysis of this general topic and evidence that the importance of this composition bias has grown over time, see John Grigsby’s job market paper.)

3. New hire wages, not aggregate wages, is what matters anyway

The third important point is that: conceptually, the average real wage of the incumbent employed – which is what we usually have data on – is not what matters anyway!

As Pissarides (2009) ECMA pointed out, it doesn’t really matter if the wages of incumbent employed workers are sticky. What matters is that the wages of new hires are sticky.

Why is this? Suppose that the wages of everyone working at your firm are completely fixed, but that when you hire new people, their wages can be whatever you and they want. Then there’s simply no reason for involuntary unemployment: unemployed workers will always be able to be hired by you at a sufficiently low real wage (or to drop out of the labor force voluntarily and efficiently). If new hire wages were sticky on the other hand, that’s when the unemployed can’t find such a job.

That is: it is potential new-hire wages that are the relevant marginal cost for the firm.

(For potential caveats on the importance of incumbent wages, see Masao Fukui’s job market paper; for related empirics, see Joe Hazell’s job market paper with Bledi Taska.)

---

Putting it all together, we have three reasons to think that the data which informed the move from sticky wage to sticky price models were misleading:

Now, maybe correcting for these, we would still find that (new-hire) real wages are not “too high” after a contractionary monetary policy shock. But this is an open question. And the best evidence from Hazell and Taska does argue for sticky wages for new hires from 2010-2016 – in particular, sticky downwards.

With that discussion of the empirical critique of sticky wage models, on to the theoretical critique.

Brief reminder: the Barro (1977) critique says that merely observing sticky nominal wages in the data does not necessarily imply that sticky wages are distortionary, because it’s possible that wages are determined as part of long-term implicit contracts.

1. So what?

But! This also does not rule out the possibility that observed nominal wage stickiness is distortionary!

We observe unresponsive nominal wages in the data. This is consistent either with the model of implicit contracts or with the distortionary sticky wage hypothesis. Based on this alone there is an observational equivalence, and thus of course this cannot be used to reject the hypothesis that sticky wages are distortionary.

Moreover, it’s unclear that we observe contracts of the type described in Barro (1977) – where the quantity of labor is highly state-dependent – in the real world, at all.

2. Circa 2021, this critique is most typically ignored anyway

The other thing to note here is: despite the concern in the 1980s about this critique of sticky wage models... we’ve ended up using these models anyway!

Erceg, Henderson, and Levin (2000) applied the Calvo assumption that a (completely random) fraction of wage-setters are (randomly) unable to adjust their wages each period. This modeling device is now completely standard – though as emphasized above only as an appendage to the baseline New Keynesian framework.

Moreover, the ascendant heterogeneous agent New Keynesian (HANK) literature often does, in fact, takes sticky wages as the baseline rather than sticky prices. See the sequence of Auclert-Rognlie-Straub papers; as well as Broer, Hansen, Krusell, and Oberg (2020) for an argument that sticky wage HANK models have a more realistic transmission mechanism than sticky price ones (cf Werning 2015).

Now maybe you think that large swathes of the macroeconomic literature are garbage (this is not, in general, unreasonable).

But this certainly does reveal that most macroeconomists today reject, at least for some purposes, the critique. Hall (2005) for example writes of, “Barro’s critique, which I have long found utterly unpersuasive.”

The history of thought here and how it has changed over time is interesting on its own, but it also suggests a natural conclusion: if you think of involuntary unemployment as being at the heart of recessions, you should start from a sticky wage framework, not a sticky price framework. The original empirical and conceptual critiques of such a framework were misguided.

More importantly, this should affect your view on normative policy recommendations:

We don’t want to stabilize P; we want to stabilize W!

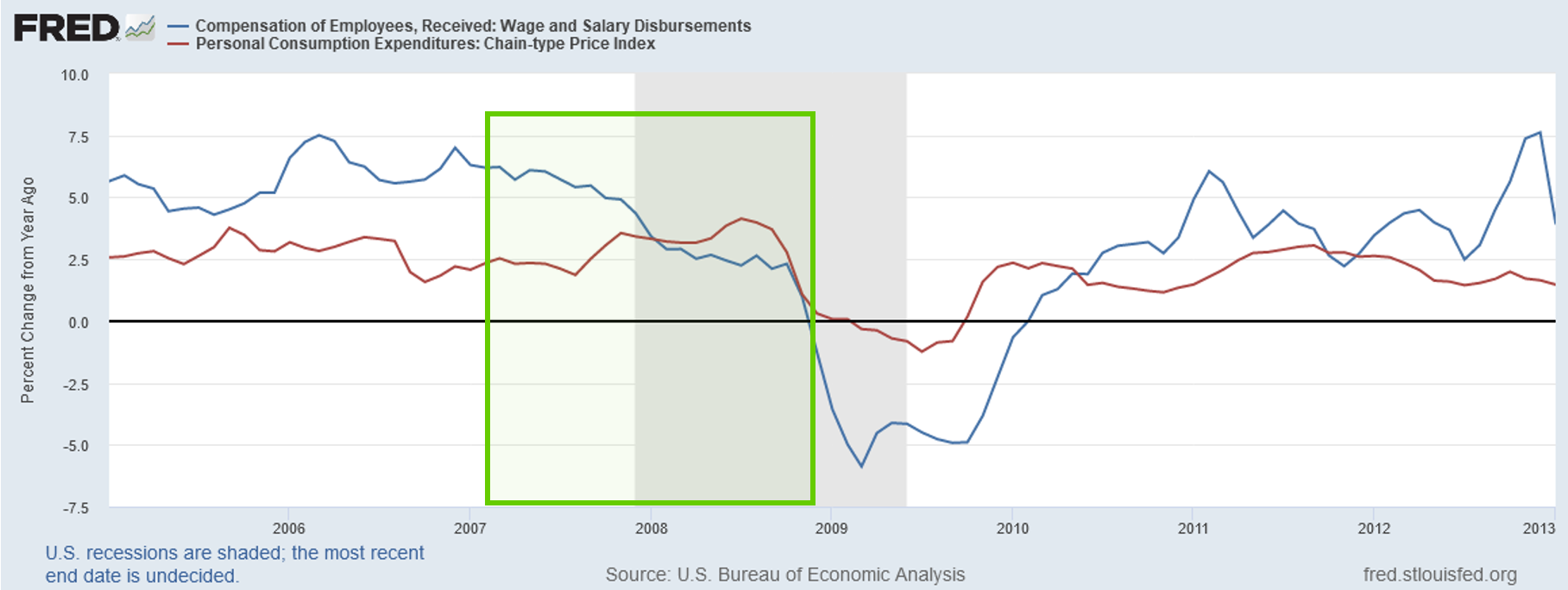

These can be quite different. Let’s cheat and note that in a model without labor force fluctuations, stabilizing nominal wages W is the same as stabilizing nominal labor income WN. Then, for example, observe in the critical period of 2007 through late 2008 – before the Fed hit the zero lower bound – nominal labor income growth (blue) was steadily declining even though inflation (red) was rising due to spiking oil and food prices.

The accelerating inflation is why we had the FOMC meeting on September 16, 2008 – the day after Lehman Brothers declared bankruptcy (!!) – and stating, “The downside risks to growth and the upside risks to inflation are both of significant concern to the Committee” and unanimously refusing (!!) to cut its policy rate from 2%.

If the Fed had been targeting nominal wages or nominal income, instead of inflation, it would have acted sooner and the Great Recession would have been, at the least, less great.

---

Finally, while I just wrote that sticky prices prescribe inflation targeting as optimal monetary policy, in fact this is not generically true. It is true in the textbook New Keynesian model, where price stickiness is due to exogenously-specified Calvo pricing: a perfectly random fraction of firms is allowed to adjust price each period while all others remain stuck.

Daniele Caratelli and I have a new paper (almost ready to post!), though, showing that if price stickiness instead arises endogenously due to menu costs, then optimal policy is to stabilize nominal wages. Under menu costs, even if wages are completely flexible, then ensuring stable nominal wage growth – not stable inflation – is optimal, just as in the basic sticky wage model.

Thanks to Marc de la Barrera, Daniele Caratelli, Trevor Chow, and Laura Nicolae for useful discussions around this topic.